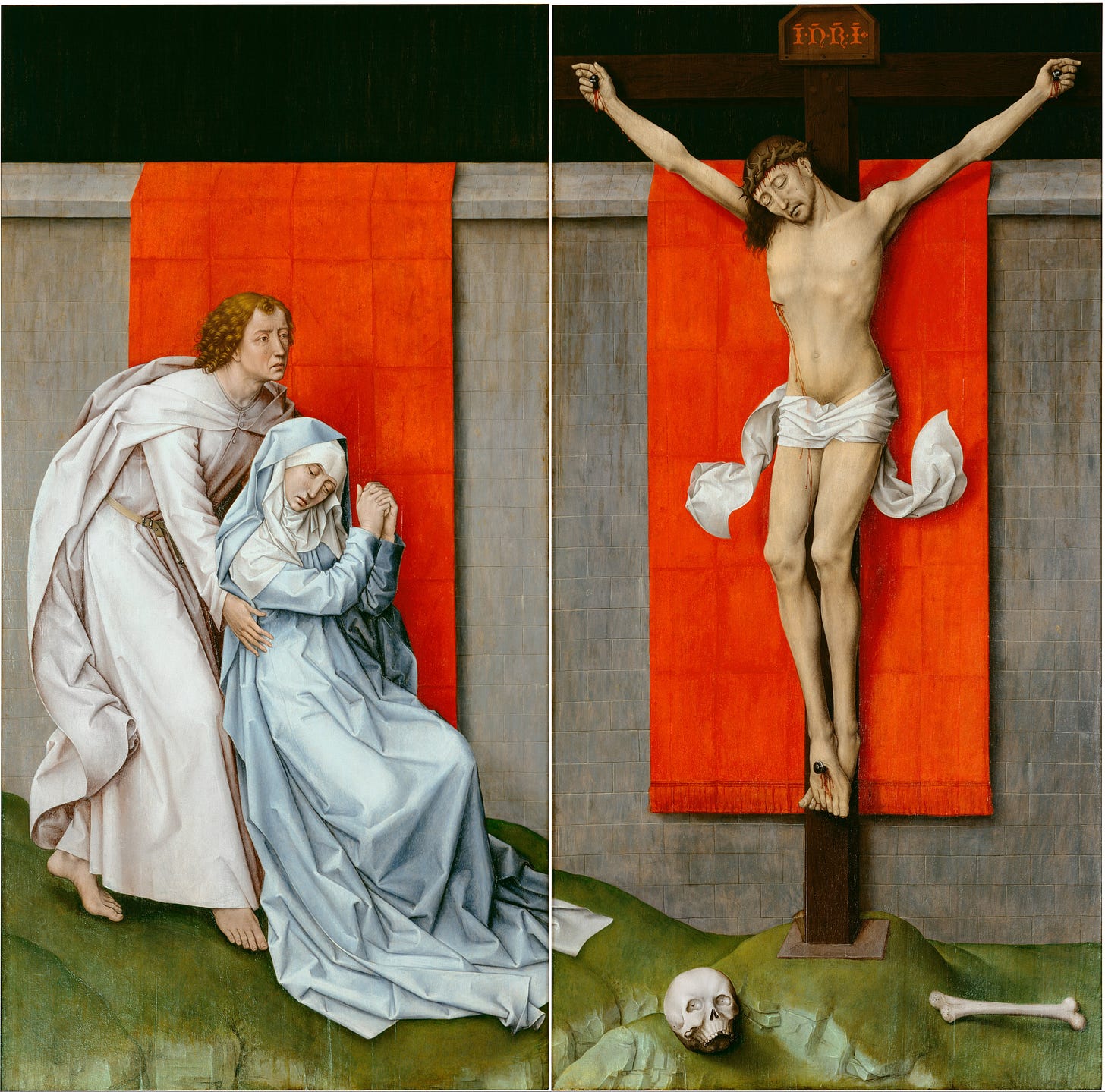

There is a sparse chapel on the second floor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Six rows of small wooden chairs face a work of sublimity: a diptych by Rogier van der Weyden. “The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning” depicts a religious scene, but van der Weyden taught me to pray in spite of the subject of this painting not because of it. One crisp fall morning of my sophomore year of college I set myself the task of spending an entire hour before a single work of art in the hopes that this exacting exercise would birth a capacity for serious art appreciation. It did much more than that.

Vocation grows like a seed from birth, it does not spring fully formed, and it cannot be planted. We have it or we don’t. If it is there it gasps for nourishment and cultivation. That hour in the chapel was the first time I threw myself into the activity that would become my life’s work: identifying and understanding the rhythms of other minds. That’s what editing is. That’s the most essential element of it, anyway.

The walk from my dorm down Locust Walk, over the bridge which straddles the Schuykil River and up the Rocky Steps I was afraid. The fear was warranted. In the hour ahead I would discover if I had the resources to stand alone, unarmed and unassisted, before a masterpiece. It is not easy to look at a painting. The exercise measures me. It takes me to task. In front of a painting I discover whether I know how to see. This beauty, this mind and soul. Can I understand it? Can I wrestle my mind out of itself up flat against this alien power?

The test I had set for myself that morning would be a referendum on precisely the qualities I value and I would have no escape from failure. It would be clear. I had experienced such failures before, traps I’d fallen into, similarly trying exercises in which I discovered midway I lacked the horsepower for completion or participation. I knew what it was like to stumble into proximity with a mind that high above mine. But I’d never done it on purpose. I knew what awaited me was too big for me to grasp. That was the challenge — would I know what to do with something I could not know. These were my thoughts as I climbed up the grand staircase to the second floor and caught my first glimpse of the red curtains which van der Weyden had painted behind his Christ, Virgin, and John. The painting is at the farthest end of the last wall on the East Wing, like the podium of a cathedral, you can see it straight ahead while galleries branch out from side to side along the long hall.

Acquaintance with the powers of a mind and soul wholly unlike mine is painful — and certainly when I was young it was more so. I was swift to jealousy and the more alien the powers were, the more jealous I was. (I am still like this — though less, I hope, all the time.) van der Weyden was punishingly strange. He leaves no sweat, there is no turbulence that he did not put there. Even the wind in his paintings is articulated in his jarring calm.

Every passage, every stroke, is delicate and fine.

One wants to call him perfect, but perfection is a slur for such a human work.

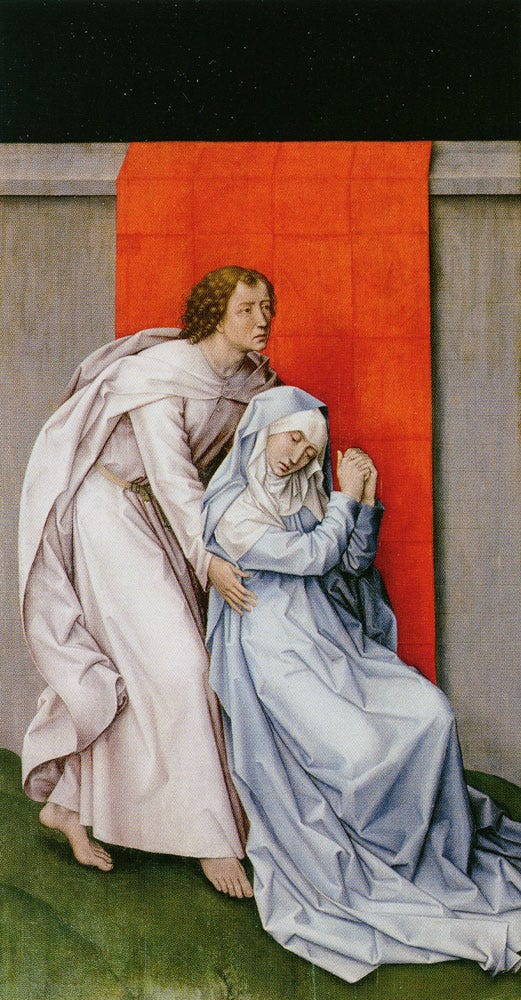

The red curtains frame the bodies, and the framing on Mary and John accentuate the flow of their forms — the motion of the painting, which pushes up and to the left, flows from them.

Look at the two panels of the diptych separately:

And then again together.

The John and Mary panel cannot stand alone. The pair need Jesus. They are drawn to and force themselves from him. Their motion is stimulated by him. But the Crucifixion is self sufficient. The only movement in the panel is the loincloth wavering in invisible air which ruffles nothing else. If not for the errant fold in Mary’s skirt which flows from one panel to the other, the crucifixion would be whole. He does not need them.

The only vibrant color is the red of the curtains and the lettering on crucifix’s wood. van der Weyden painted creases on each cloth to show that they had been folded neatly into squares. Why? There is so little incident in the painting, the creases assert themselves not only because they mar the vibrant red, but because they are incongruously commonplace and bespeak a human activity alien to the rest of the context.

The pitch black field behind and above the wall establishes the scene in a strange world. There is grass on the ground but there is no sky, no trees. This is not a familiar planet. Why didn’t van der Weyden extend the wall to the top of the canvas? Cover the black with your hand. Without it, the scene feels familiar, contained. The black atmosphere places it beyond our ken.

The most difficult part of the painting for me has always been the delicacy of the bodies. Jesus is so thin, it is impossible for me to render the fragility of his body with my pencil in my sketchbook. I have never tried to paint any piece of it, though I have imagined many times how frustrating it would be to set myself the task of proving my own clumsy incapacity. Look! The knee sockets bulge beneath tight flesh, marked only by faint shadow. His biceps yawn from shoulder to jutting elbow bone. How can the flesh contain blood? There is hardly space between it and the encased skeleton.

It is always my practice to stand before a painting with an open sketch book, translating the painter’s vernacular from his or hers to mine. I do this to understand them, to force myself away from me and into them. I can’t help that the study is always translation — translation is as close as I can get to the original. It’s either translation or introspection. This way expansion is possible.

It is not a viewer’s job to edit the painting. Appreciation has to proceed criticism. But this is also true of editors. The first step in editing is to appreciate first how the mind that made the work meant for it to be whole. A person cannot be an editor if she is not excited by the possibility of close acquaintance with a different way of seeing and thinking. The beauty invites participation. Viewing paintings always is participatory. it demands action, commingling. That is what van der Weyden taught me to do.

P.S. paintings make great gifts! You can buy mine here: celestemarcus.com

Here are some recent one:

s

:

‘One wants to call him perfect, but perfection is a slur for such a human work’ - on point