On two floors of a building on the east side of Manhattan, seventy works work on the viewers with the wherewithal to make it to the Galleria Mattia De Luca for the Giorgio Morandi: Time Suspended II exhibition. The effect over the hours that the accumulative rooms worth of masterworks has is a peculiar hypnosis. This is because the works demand concentrated attention: Morandi is subtle, geometrically complex, and delicious. The volume of works allow (or force) viewers to enter into his strange, exacting universe.

Morandi was an Italian painter who lived from 1890 to 1964, but he could have lived at any time and in any place - so long as paint and light and the rudimentary tools he needed to consider the two together were at hand.

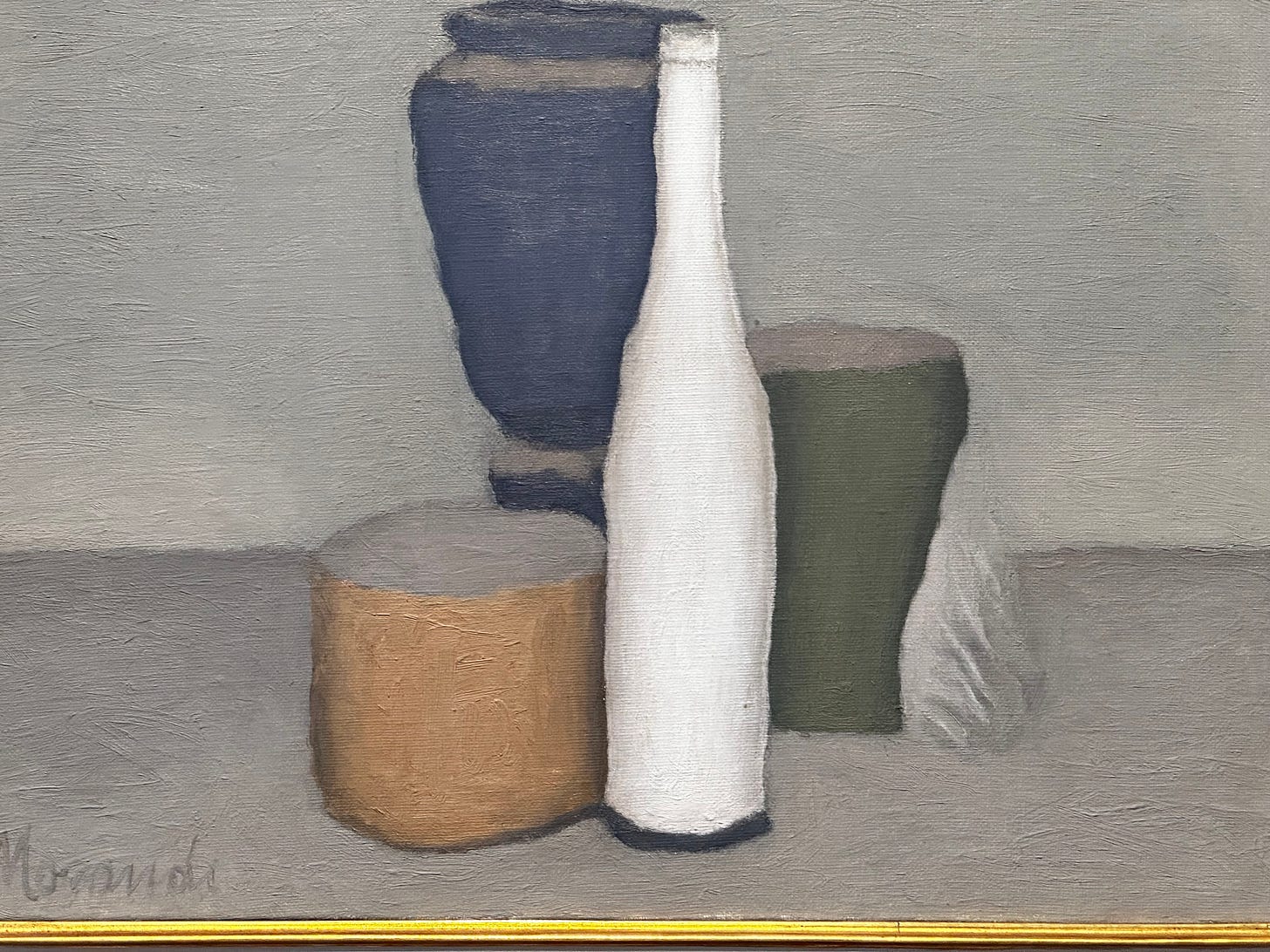

The exhibition contains a handful of landscapes and three handfuls of flower still life (among the most exquisite and particular flowers to have ever been articulated in oils) but the vast majority of the rooms are lined with canvas after canvas of ceramic and glass bottles, cups, bowls, and the occasional glint or cut of cutlery arranged in compositions and set inside the frame of the painting in what the viewers comes to learn is an extremely calculated manner.

Three considerations demand scrutiny:

The intimacy of one object in relation to another. Morandi doesn’t paint edges, he suggests them. The end of, say, a pitcher is indicated by the direction of the light falling onto the cut or motion of the pitcher’s clay, and also the way that the glass or the bowl or the table beside it meets that edge.

The shadow from one object falls to the foot of another and that dark cast cuts against the edge of the adjacent vessel, thus establishing it. Morandi doesn't offer the mercy of explication. The result is a painterly monism: each is each, indivisible."

The luscious layering of the paint. Morandi was intoxicated by the feel of paint on canvas. Because Morandi does not offer the relief of clearly defined edges, viewers must learn to study carefully the direction of his brush. The same hue of the same color can teem with incident.

He expects his viewers to pay attention to the application of the paint. Morandi painted wet, and the canvas was meant to show his sweat, his work in the moment, the way the paint made his blood rush, every idea that came into his quick, fine mind and then immediately into movement in his hand. To study him is to learn the tempo and tendency of his attention and his hand. That is an intimacy too. This motion gives the gentle paintings an energy.

The geometry. Morandi preferred sleepy colors and the dulcet hues lull us into overlooking the rigor of his compositions. Over the course of the exhibition, awe for the calculations which undergird Morandi’s compositions swells. How did he sustain such meticulous attention?

The attention is even more impressive because it is lavished on every stroke in paintings of such simple objects. He makes us unlearn what we know of these quotidien vessels because he uses them like numerals in a mathematical consideration of space and volume. We have seen flowers in a vase but we have never seen them this way. We have never trained ourselves to see the complexities of the geometries which make them up — and if we have, not in this manner, not with such rigorous attention.

Morandi’s flowers do not depend on the viewer’s association with floral beauty. He undoes our conception of a rose and teaches us a new one. His roses are flaps and folds of one hue on top of another. The edge of each petal establishes itself beside the other. The bouquet is organized into a pleasing, balanced composition. He makes demands of his beauty, and it makes demands of us.

Thanks for alerting me to this show! The gallery requires appointments in advance?